There was a time when a pound of bacon was a pound of bacon. And we still call it a pound of bacon. But the reality is that a package of bacon now weighs only 375 grams, not 454 grams which equals a pound. That’s an 18% reduction in package size. However that’s only half of the shrinkflation story.

From 2019 to 2022 in Canada the average price for 500 grams of bacon has risen from $7.06 to $8.55, a 21% increase in the price per gram.

That is shrinkflation. The subtle, and sometime not so subtle, reduction in package size combined with a commensurate increase in price for the smaller package.

At a time when inflation is rising, interest rates are increasing, the economy is slowing, and people are struggling, when did shrinkflation become acceptable?

Shrinkflation Defined

According to Wikipedia, shrinkflation is “also known as the grocery shrink ray, deflation, or package downsizing, is the process of items shrinking in size or quantity, or even sometimes reformulating or reducing quality, while their prices remain the same or increase.”

From a company’s viewpoint this is a way for them to reduce costs and/or increase profitability. It does not take a lot of reengineering to reduce the amount of goods that go into a product and it does not take a lot to increase unit prices.

The severity of the impact of this practice from a consumer’s viewpoint however is that they are simply paying more for less, particularly at a time when they have less money to pay with. It would be one impact to pay the same for fewer goods, or pay more for the same amount of goods, but the compounded impact of both paying more while getting less is what makes this practice harmful.

What is even more disappointing is that this practice is almost never done openly and overtly. For many consumers they may not even notice because the changes are not always apparent.

It’s only if you pay close attention to the price changes over time, and the package size changes over time, that you realize that there is a covert marketing strategy at play to pull the wool over consumers eyes.

Examples

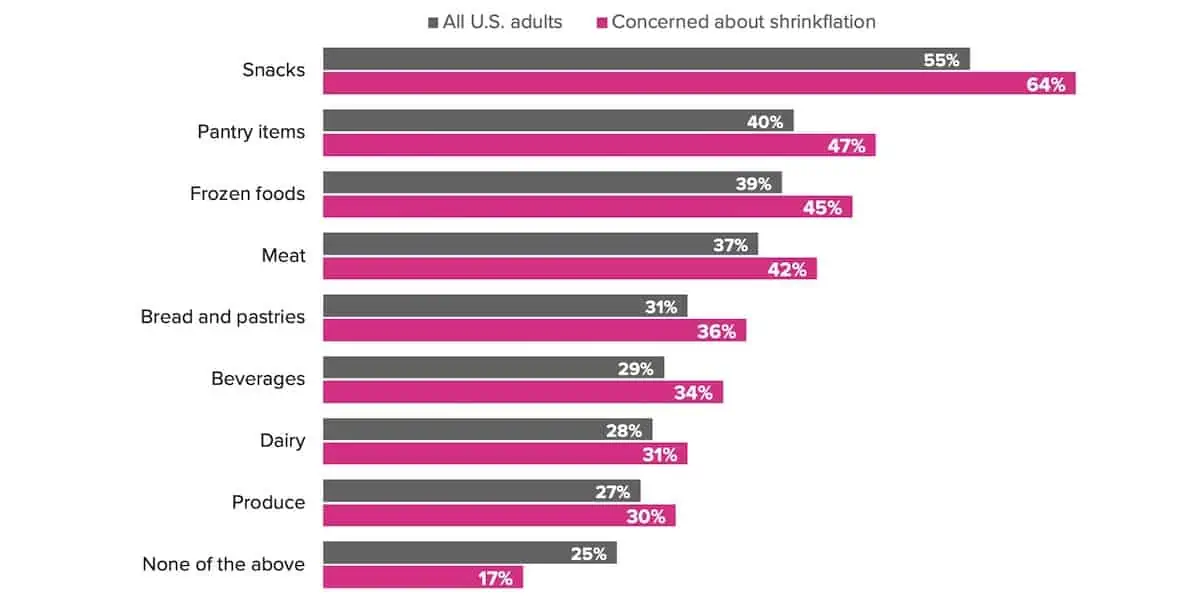

Morningconsult.com reports that the impacts of Shrinkflation are being seen across a wide variety of grocery categories.

There are so many examples of products that have been subject to shrinkflation that it is simpler for us to list sources. Note that we have only listed product package sizes here. There are still compounding price increases to be considered.

1. Buzzfeed

Examples include:

- Corn Flakes reduced from 760 grams to 600 grams

- Lemonade reduced from 1.75 litres to 1.53 litres

- Dove Soap reduced from 113 grams to 106 grams to 90 grams in 3 years

- All detergent reduced from 1.18 litres to 946 millilitres

- Pringles reduced from 200 grams to 180 grams to 165 grams

2. Investorplace.com

Examples include:

- Cadbury Dairy Milk bar reduced from 200 grams to 180 grams

- Domino’s Chicken wings serving reduced from 10 to 8 pieces

- Gatorade reduced from 32 ounces to 28 ounces

3. Marketrealist.com

Examples include:

- Folgers Coffee reduced from 51 ounces to 43.5 ounces

- Kleenex reduced from 65 tissues to 60 tissues

The examples are endless. In fact it is reasonable to believe that most products in your grocery store aisles are subject to shrinkflation. Either prices have increased with smaller or the same packages sizes, or prices have stayed the same with smaller package sizes.

Are there really any products that cost the same with the same package size? It is not obvious what these obscure products are.

Projections and Actions

It is said that the practice of Shrinkflation has been around for decades. I certainly have the clear memory of products and goods from my childhood being much cheaper, and a vague memory of those same goods being in larger packages.

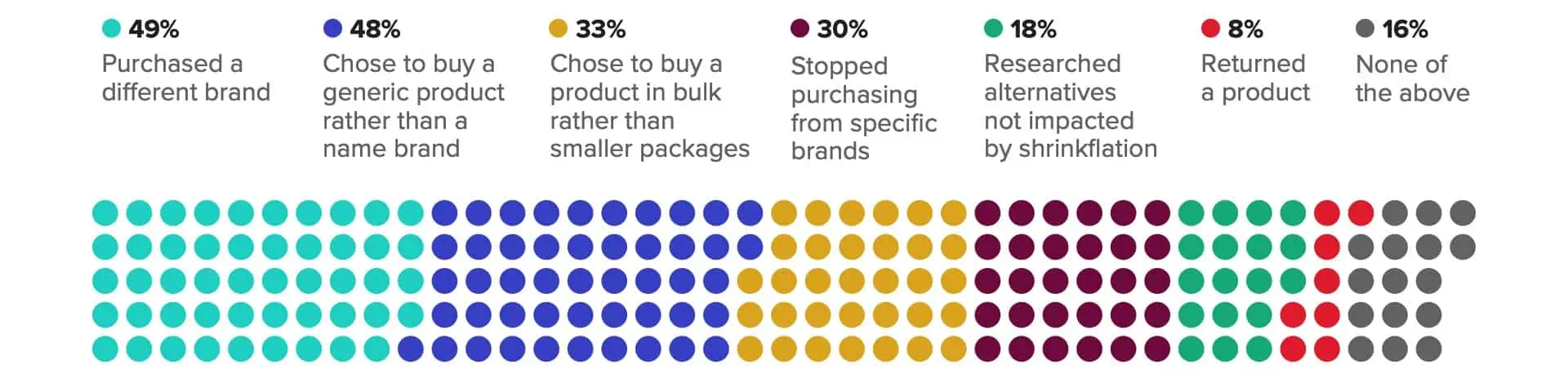

According to CNBC.com, 64% of consumers are concerned about Shrinkflation and as such they are taking steps to offset these marketing tactics. Customers are buying cheaper brands, looking for generic brands or alternative products, buying product in bulk, or stopping purchases altogether.

The following graphic from morningconsult.com shows how consumers are responding:

With respect to the future it is hard to believe that companies will decide to reverse the trend. From their perspective why should they increase package sizes and reduce prices? They won’t!

Alternatively companies will increase their focus on advertising and marketing to manage consumer attractiveness to and motivation to buy their products. And for the most part this will prove effective enough that the companies will be able to hold their ground on the shrinkflation actions that they have taken.

Even severe shifts in consumer purchasing patterns are not likely to be long live enough, or drastic enough, to cause companies to reverse course on these tactics.

And this is unfortunate because at the same time that this marketing game is being played out, the factors and dynamics that put pressure on company costs and profitability in the first place will be dissipating.

High freight costs that were incurred during the pandemic will come down. High raw material costs, high manufacturing costs, and high energy costs will also come down over time. Supply-demand imbalances and bullwhip effects will dampen over time.

And when Supply Chain gets back to more “normal” operation in a post-pandemic world, company interests can be served without the need to continue with Shrinkflation.

Conclusion

Unfortunately improvements in Supply Chain performance and costs will not be enough to curtail the Marketing strategies to perpetuate the deployment of Shrinkflation tactics.

All of that will mean that company costs will naturally reduce, and there will be a commensurate increase in profitability without the need for shrinkflation actions.

But history has shown that over the long term companies will continue to reduce package sizes and increase prices at every opportunity. They will very seldom do the opposite.

Unless there is an unprecedented outcry from consumers, and they “vote” with their wallets by not rewarding Shrinkflation practitioners with their business, this practice will continue.

So many of the affected products are essential to the standard household grocery list. But for those items that are discretionary purchases, perhaps that is where consumers will have the greatest opportunity for mitigating Shrinkflation practices.

It’s only a matter of time when a dozen eggs will not include 12 eggs any more, but it will cost a lot more anyways and they will still call it “a dozen eggs”.